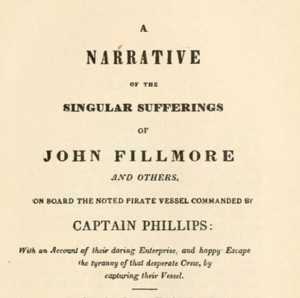

Two hundred and ninety one years ago today — on August 29, 1723 — a young fisherman on his first voyage at sea was captured by a small pirate crew off the coast of present-day Canada. That fisherman was John Fillmore, who would become the great-grandfather of the future U.S. president, Millard Fillmore. Just twenty-two years old, Fillmore had grown up near Ipswich, Massachusetts, a small coastal village about twenty-five miles north of Boston. The stories brought back to the village by men who worked at sea had a powerful impact on the young man’s desire to set sail himself: “hearing sailors relate the curiosities they met with in their voyages, doubtless had a great effect, and the older I grew the impression became the stronger,” Fillmore recalled.

Two hundred and ninety one years ago today — on August 29, 1723 — a young fisherman on his first voyage at sea was captured by a small pirate crew off the coast of present-day Canada. That fisherman was John Fillmore, who would become the great-grandfather of the future U.S. president, Millard Fillmore. Just twenty-two years old, Fillmore had grown up near Ipswich, Massachusetts, a small coastal village about twenty-five miles north of Boston. The stories brought back to the village by men who worked at sea had a powerful impact on the young man’s desire to set sail himself: “hearing sailors relate the curiosities they met with in their voyages, doubtless had a great effect, and the older I grew the impression became the stronger,” Fillmore recalled.

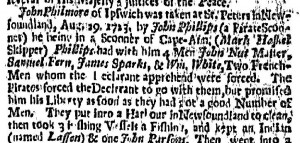

In the summer of 1723, Fillmore took his first job at sea, working aboard the fishing schooner Dolphin. It was on August 29 that the Dolphin was captured by a crew of pirates under the command of a man named John Phillips. Phillips and four other men had been part of a fishing crew working near Newfoundland when, only days before, they deserted their captain in a stolen schooner and set out as pirates. The Dolphin was one of the pirate Phillips’ first captures.

John Fillmore would sail as a captive aboard Phillips’ ship for eight long months — one of many men forced aboard pirate ships during this era, as I recount my new book, At the Point of a Cutlass. The pirate John Phillips had a temper so violent, Fillmore later recalled, that even members of his own crew hated him — and some even tried, unsuccessfully, to desert. “Phillips was completely despotic,” Fillmore recalled, “and there was no such thing as evading his commands.” Phillips nearly sliced Fillmore’s head off with a sword at one point and threatened to kill him at another, but Fillmore and several other captives were ultimately able to stage one of the most successful uprisings in the history of Atlantic piracy.

The break Fillmore and the other captives were desperately looking for came in April 1724. By now, Phillips’ crew had sailed to the Caribbean and back, returning again to the coast of Nova Scotia. They captured a sloop, the Squirrel, and took the new vessel as their own, moving their equipment, supplies, and weapons over the next day. The pirates allowed most of the captured sloop’s crew to go free, but kept its young captain, Andrew Harradine, from Gloucester, Massachusetts. Within a day of Harradine’s capture, Fillmore quietly approached him with the idea of planning an attack on the pirate crew. There were seven captives in on the plot, including Fillmore and Harradine, and it seemed possible that they might be able to overpower the eight pirates if circumstances were right.

The break Fillmore and the other captives were desperately looking for came in April 1724. By now, Phillips’ crew had sailed to the Caribbean and back, returning again to the coast of Nova Scotia. They captured a sloop, the Squirrel, and took the new vessel as their own, moving their equipment, supplies, and weapons over the next day. The pirates allowed most of the captured sloop’s crew to go free, but kept its young captain, Andrew Harradine, from Gloucester, Massachusetts. Within a day of Harradine’s capture, Fillmore quietly approached him with the idea of planning an attack on the pirate crew. There were seven captives in on the plot, including Fillmore and Harradine, and it seemed possible that they might be able to overpower the eight pirates if circumstances were right.

Their chance came close to noon on April 18 as the pirates sailed north. Fillmore and Harradine were standing on the deck with several of the other pirates. Fillmore stood casually spinning a broad axe that was lying on the deck with his foot. Then, in an instant, the men attacked. One captive grabbed the pirate standing next to him and threw him overboard. Fillmore bent over and picked up the broad axe at his feet and bore down on another of the pirates who was busy cleaning his gun, striking him over the head and killing him. Alarmed by the shouts and commotion on deck, Captain Phillips came out of his cabin to see what was going on. The captive who was manning the tiller, a Native American named Isaac Lassen, jumped at Phillips and grabbed his arm while Harradine struck him over the head with an adze. Finally, two French captives jumped a fourth pirate, killed him, and threw him overboard.

The remaining pirates were now far outnumbered and immediately surrendered. Fillmore and the other captives took control of the ship and headed home, arriving in Boston harbor on Sunday, May 3. The captives’ stunning overthrow of the pirate crew fascinated the town. The Boston News-Letter, the Boston Gazette, and the New England Courant each published accounts of how Fillmore and Harradine brought down Phillips and his men. Two members of Phillips’ crew, William White and the quartermaster John Rose Archer, were convicted and hanged. After the execution, the bodies of White and Archer were hauled back out to Bird Island in Boston Harbor (Bird Island no longer exists today, once standing where Logan Airport is today). White was buried on the island, while Archer’s body was hung there in a gibbet “to be a spectacle, and so a warning to others.”

At the Point of a Cutlass was released in June 2014 and is on sale now.