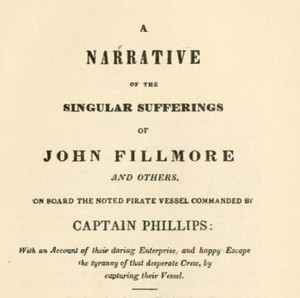

On Saturday, March 9, 1723, a young fisherman named Philip Ashton — captured by pirates nine months before — was standing on the deck of a schooner when he saw a longboat approaching with seven of the pirates aboard. The men were rowing in the direction of the island of Roatan to collect fresh drinking water. Ashton called out to the ship’s cooper in the longboat, asking if they were going ashore. Yes, the cooper answered, they were. Ashton asked if he could go with them. The cooper hesitated, suspecting the pirate captain, Edward Low, would be furious if Ashton were allowed to go to the island. But Ashton kept arguing. “I urged that I had never been on shore yet, since I first came on board, and I thought it very hard that I should be so closely confined, when everyone else had the liberty of going ashore.”

So the cooper agreed to take him, “imagining, I suppose,” Ashton later recalled, “that there would be no danger of my running away in so desolate uninhabited a place as that was.” Ashton quickly climbed down and into the longboat. Ashton took nothing with him when he climbed into the boat, not even a pair of shoes. But by the time he spotted the approaching longboat, it was too late. This, Ashton thought, was the chance he had been waiting for, and he did not want to miss it or to give the cooper any reason to suspect what he had in mind.

So the cooper agreed to take him, “imagining, I suppose,” Ashton later recalled, “that there would be no danger of my running away in so desolate uninhabited a place as that was.” Ashton quickly climbed down and into the longboat. Ashton took nothing with him when he climbed into the boat, not even a pair of shoes. But by the time he spotted the approaching longboat, it was too late. This, Ashton thought, was the chance he had been waiting for, and he did not want to miss it or to give the cooper any reason to suspect what he had in mind.

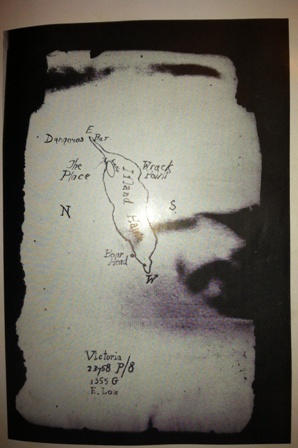

The men continued to row the boat in toward the shore. The long island of Roatan is made up of a series of tall, mountainous hills, and the peaks towered above the men as they made their way to land. At many points along the shoreline of Port Royal harbor the land rose sharply from the water, forming steep, rocky walls. Thick patches of bush and trees clung to the tops of these walls and blanketed the hills as they reached to the sky. But at a few points along the shore, the valleys between the tall hills gave way to some small patches of flatter ground, and at several of these spots Ashton could make out some narrow strips of beach scattered along a roughly half-mile curve in the middle of Port Royal harbor. The cooper and his men rowed their boat up to one of these beaches where, hidden behind the slight rise of the sand, was the mouth of a freshwater creek, a small run no more than ten feet wide and almost completely concealed by the thick woods, where the water ran gently down from springs high in the hills. The men beached the boat and climbed ashore.

Getting out of the boat, Ashton’s bare feet touched the sandy ground. The beach was narrow and coarse, a slight rise of brown sand, pebbles, and shells that was just four or five feet wide between the water line and the beginning of the thick growth of grass and weeds. The beach ran along the water for close to a hundred yards. Just over the slight hump of the beach, not even two paces from the harbor’s edge, was the mouth of the creek, slowly running under a thick, green canopy of leaning palm trees and large bushes. Ashton helped the men drag the heavy wooden casks onto shore and rolled them over the beach and to the edge of the creek. The creek was shallow, just one or two feet deep in most places, with gently sloping edges. Ashton lay down by the trunks of some palms and mangroves lining the edge of the creek and lowered his head, taking a long drink of the cool, fresh water.

Filling the casks took some time. As the men worked, Ashton stepped back out onto the beach and started walking slowly along the sand, stopping occasionally to casually pick up a stone or shell as he moved away from the men. As the distance between Ashton and the men grew, Ashton edged slightly closer to the woods that bordered the beach. The cooper looked up and called out to him—where did he think he was going? Ashton said he was going to look for coconuts, since some coconut trees were growing near the beach. That seemed to satisfy the pirates for the moment. Ashton kept walking.

Filling the casks took some time. As the men worked, Ashton stepped back out onto the beach and started walking slowly along the sand, stopping occasionally to casually pick up a stone or shell as he moved away from the men. As the distance between Ashton and the men grew, Ashton edged slightly closer to the woods that bordered the beach. The cooper looked up and called out to him—where did he think he was going? Ashton said he was going to look for coconuts, since some coconut trees were growing near the beach. That seemed to satisfy the pirates for the moment. Ashton kept walking.

In an instant, Ashton turned away from the water and into the woods. The woods along the beach were so thick that within a dozen steps, he was completely hidden by the dense overgrowth. As quietly as he could, Ashton stepped over the roots, sticks, fallen palm branches, and dry leaves carpeting the ground. He tried to run more quickly, but the sharp broken sticks lying on the ground pierced his bare feet, and the crisscrossing web of bushes and vines made it impossible to move in a straight line. At points the overgrowth formed a barrier so thick he had to crawl on his hands and knees to get past. “I betook myself to my heels, and ran as fast as the thickness of the bushes and my naked feet would let me,” Ashton wrote.

Eventually the men finished filling each of the casks and called out to Ashton to tell him they were leaving. Ashton heard them but didn’t answer. The men started shouting for him. Between their calls, Ashton picked up bits of their conversation: “the dog is lost in the woods and can’t find his way out,” said one. Before long they realized Ashton planned to stay hidden. “He is run away and won’t come again,” a voice said. Soon after, the men headed back out towards the pirate ships and, within hours, the pirates sailed away.

The reality of Ashton’s situation was that he was not only alone on Roatan, at the time an uninhabited island off the coast of Honduras, but that he had marooned himself with practically nothing. “I was upon an island from whence I could not get off,” Ashton wrote. “I knew of no humane creature within many scores of miles of me; I had but a scanty clothing, and no possibility of getting more; I was destitute of all provision for my support, and knew not how I should come at any; everything looked with a dismal face.”

– – – – – – – – – – – – –

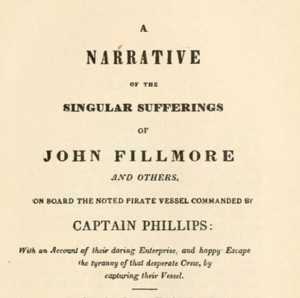

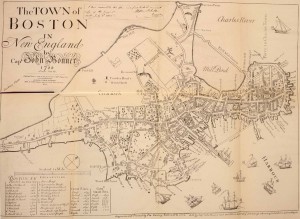

Read more about Philip Ashton’s adventures as a pirate captive and castaway in my book, At the Point of a Cutlass. I’ll be speaking at the State House in Boston on Tuesday, May 23 about my book and the many surprising connections bietween Atlantic piracy and colonial Boston. For details, click here.

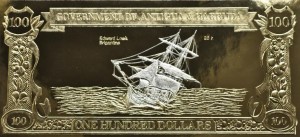

In a world where huge container ships, aircraft carriers, and cruise ships often exceed 1,000 feet in length, it’s hard to even comprehend battling a stormy ocean and massive waves in wooden vessels that were barely 50 feet long. Yet many of the fishing vessels I wrote about in my book, At the Point of a Cutlass — fishing boats that sailed in practically every month of the year from New England to the Canadian coast — were only 50 or 60 feet in length. The wooden sloop sailed in 1820 by Nathaniel Palmer from Stonington, Connecticut all the way to the bottom of South America, to just below the Antarctic Circle, was less than 50 feet long. Shipwrecks were common, and it’s a wonder many of these vessels survived.

In a world where huge container ships, aircraft carriers, and cruise ships often exceed 1,000 feet in length, it’s hard to even comprehend battling a stormy ocean and massive waves in wooden vessels that were barely 50 feet long. Yet many of the fishing vessels I wrote about in my book, At the Point of a Cutlass — fishing boats that sailed in practically every month of the year from New England to the Canadian coast — were only 50 or 60 feet in length. The wooden sloop sailed in 1820 by Nathaniel Palmer from Stonington, Connecticut all the way to the bottom of South America, to just below the Antarctic Circle, was less than 50 feet long. Shipwrecks were common, and it’s a wonder many of these vessels survived.