Two rocky islands known as the Cow (largest) and the Calf (smallest, in foreground), off Roatan, Honduras. Howard Jennings claimed to have found buried treasure on the larger island.

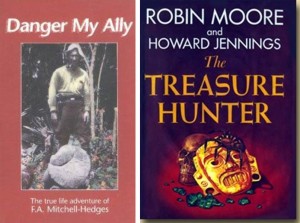

One of the first explorers to go digging on Roatan was an English adventurer named Frederick Mitchell-Hedges, who scoured the eastern end of Roatan and several neighboring islands looking for native artifacts in the early 1930s. Mitchell-Hedges found many stunning items, including jade figurines, pottery, and sculptures, some of which are still held today by the National Museum of the American Indian. But critics have questioned Mitchell-Hedges’ qualifications as an archaeologist and the legitimacy of his finds. In his Historical Geography of the Bay Islands, Honduras, William Davidson says Mitchell-Hedges would have been a “good subject” for an “exposé of pseudo-archeologists in Middle America”. And one life-long resident of Roatan told me that Mitchell-Hedges did not discover a gold statue he purportedly brought back to America; instead he bought it from an islander for $100 and a bag of flour. (Mitchell-Hedges is best known for a “pre-Columbian” crystal skull purported to have been found on the Central American mainland, but the authenticity of that piece has also been questioned based on subsequent microscopic investigation.)

A carved stone bead found by Frederick Mitchell-Hedges on Roatan in the 1930s. See collections detail at the National Museum of the American Indian (www.nmai.si.edu).

Several decades later, two treasure hunters named Howard Jennings and Robin Moore, who had heard about the Mitchell-Hedges discovery, went back to Roatan. They explored the area around Port Royal harbor, at the eastern end of Roatan, and found a number of old items — cannonballs, brass buttons, shoe buckles, and (reportedly) a buried chest holding a gold necklace, a gold ring, and some silver Spanish pieces of eight, blackened from years of exposure to moisture. The explorers also searched a pair of two rocky islands that lie within Port Royal harbor, known as the Cow and the Calf. Jennings claims to have found on the larger of these two islands another box containing a pair of old leather boots, a corroded navigational quadrant, some silver ingots, and a small leather pouch containing several handfuls of gold nuggets. Even today, rumors of buried treasure persist on Roatan. But not everyone who is familiar with the island and these treasure hunters is convinced that these stories are true.

Several decades later, two treasure hunters named Howard Jennings and Robin Moore, who had heard about the Mitchell-Hedges discovery, went back to Roatan. They explored the area around Port Royal harbor, at the eastern end of Roatan, and found a number of old items — cannonballs, brass buttons, shoe buckles, and (reportedly) a buried chest holding a gold necklace, a gold ring, and some silver Spanish pieces of eight, blackened from years of exposure to moisture. The explorers also searched a pair of two rocky islands that lie within Port Royal harbor, known as the Cow and the Calf. Jennings claims to have found on the larger of these two islands another box containing a pair of old leather boots, a corroded navigational quadrant, some silver ingots, and a small leather pouch containing several handfuls of gold nuggets. Even today, rumors of buried treasure persist on Roatan. But not everyone who is familiar with the island and these treasure hunters is convinced that these stories are true.

At the Point of a Cutlass, out in paperback this week, is on sale now.

See the new National Geographic article on the Honduras discovery here.