This month marks the 333rd anniversary of the birth of John Barnard, an adventurous New Englander whose curiosity about the world broke the mold of the traditional Puritan minister. Barnard spent hours talking with sea captains who arrived in colonial Marblehead, Massachusetts in the early 1700s, fascinated by their work and strategies for selling the tons of fish caught by local fishermen. In his younger years, Barnard never passed up a chance to travel. He sailed to Barbados and England in 1709 and, two years before, in May of 1707, Barnard sailed as a chaplain when a large fleet left Boston to attack a French fort in Nova Scotia. That was the trip that got him into trouble.

Intensely curious, Barnard spent much of his time in Nova Scotia talking with military leaders about battle strategy and sketching a map of the area around the fort. The fleet of more than two dozen vessels had been charged with taking the French fort at Port Royal (now called Fort Anne in Annapolis Royal), on the western edge of Nova Scotia, facing the Bay of Fundy. In the end, the colonists never attacked the fort and ended up leaving after only a few weeks. But one day, as the men were relaxing, Barnard joined them in a game of cards — something a chaplain, at that time, should never have been caught doing. This landed the young pastor in hot water with Cotton Mather, America’s foremost Puritan minister, when the troops arrived back in Boston. Mather publicly disciplined Barnard for the “scandalous game of cards,” and Barnard later noted that he suffered “my share of obloquy for a little piece of imprudence while I was absent, for which my pastors treated me cruelly for reasons best known to themselves.”

Barnard became the minister of the First Church in Marblehead in November of 1715. He was a major force in the history of the small fishing village. Barnard found it frustrating that the salt cod caught by Marblehead fishermen was sold by merchants in Salem or Boston, who kept the profits for themselves, even as many of the local fishermen borrowed heavily on credit to pay for food and clothing and spent most of their lives in debt. Barnard described the fishermen in his community as “slaves that digged in the mines,” and he set out to change this. Barnard loved to fish himself and was fascinated by the trade. He found it easy to talk to the men who worked in the harbor, including captains from foreign ports who came to Marblehead to load their ships with fish. He learned as much as he could about the salt cod trade and urged local ship owners to start exporting the catch themselves rather than through middlemen in Salem or Boston. After some initial reluctance, Marblehead ship owners began exporting their catch directly to Europe and the Caribbean. Not long after, Boston merchants complained they were “almost entirely stripped” of cod exports because the trade was now “confined to the fishing towns who generally send it abroad in their own vessels, especially Marblehead, Salem, and Plymouth.”

Barnard also pursued the incredible story of Philip Ashton, a young Marblehead fisherman who was captured by pirates in 1722 and then escaped on an uninhabited Caribbean island where he lived alone as a castaway for close to two years. When Ashton reappeared after his three-year odyssey — to a village that had given him up for lost — Barnard recorded the young fisherman’s amazing story and used it as a basis for his Sunday sermon the very week Ashton arrived home. Ironically, Barnard preserved Ashton’s story not for the sake of history but because he believed it contained a powerful religious message. Like many Puritan ministers at the time, Barnard worried about a weakening of faith in his community and a disregard for the teachings of the church — “they were,” he wrote of Marblehead during his early years there, “generally as rude, swearing, drunken, and fighting a crew as they were poor.” But Ashton’s story, Barnard believed, offered a real-life example he could hold up as proof that God watches over and protects people, even an ordinary fisherman. “In you, we see that our God whom we serve is able to deliver out of the fiery furnace and from the den of lions!” Barnard proclaimed in his sermon that Sunday in May, 1725. “In you, we see that nothing is too hard for the Lord and that ’tis not in vain for us to call upon Him!”

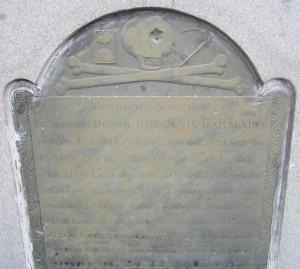

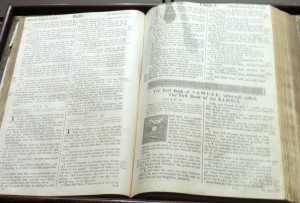

Later that summer, Barnard published a full narrative recounting Ashton’s incredible journey, a fascinating and rare document that forms the core of my new book, At the Point of a Cutlass. Barnard lived and worked in Marblehead until his death at age eighty-eight in 1770. He is buried high on the rise of on Old Burial Hill in Marblehead, overlooking the harbor. The large Bible that Barnard used during many of his years in Marblehead still sits at the front of the First Church today.

At the Point of a Cutlass was released in June 2014 and is on sale now.